Today the RTPI published its first Practice Advice Note on Artificial Intelligence (AI). In this blog, Dr Daniel Slade, Head of Practice and Research at the RTPI, argues that a 2375-year-old work of philosophy brings useful insights into the planning profession’s relationship with AI.

AI boomers, AI doomers, and what it all means for the planning profession

There’s widespread agreement that AI-related technologies, and our collective response to them, will have a huge impact on society and the environment. Whether these changes are positive or negative is a subject of huge debate.

There’s widespread agreement that AI-related technologies, and our collective response to them, will have a huge impact on society and the environment. Whether these changes are positive or negative is a subject of huge debate.

For enthusiasts, techno-utopians, and AI ‘boomers’, the technology will bring more efficient public services, drive economic growth, make individuals’ lives easier, and advance research and development.

On the other side of the debate are the sceptics and ‘doomers’. They point to the fact that AI brings serious disinformation, copyright, and intellectual property concerns. Systems may be prone to ‘algorithmic bias’, while AI data centres use huge amounts of water and energy. Academic research suggests that generative AI may lead to a loss in the quantity and earnings of white-collar jobs.

The truth is likely to be somewhere in-between. For good and for bad, AI will hugely impact the wider world planners work in. And our advice note walks readers through the practical opportunities and risks that AI brings for planners in particular. But what does this mean for the planning profession as a whole? And to what extent should work currently being done by planners be done by AI?

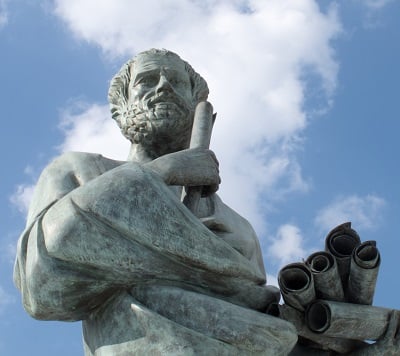

To answer these questions, we need to drill down to a simple but fundamental question: How do planners make decisions? To do so, we have to go to go back to basics. Or, more specifically, to the Athenian lyceum in 2375 BCE.

What Aristotle tells us about how planners make decisions

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argued that there were three types of wisdom: episteme, techne and phronesis.

First, episteme. We see echoes this of this word in the English terms ‘epistemic’ and ‘epistemology’. It concerns universal, scientific knowledge about why the world works as it does. The laws of physics are one example. For planners, this may include economics, demographics, or ecology.

Techne was Aristotle’s second type of wisdom, with echoes in the English words ‘technology’ and ‘technique’. It refers to the technical application of knowledge towards a specific goal. For planners, this could be knowing how to use GIS for plan making or knowing the key stages of submitting a planning application.

Aristotle’s third type of wisdom is phronesis. There are no easy parallels for this concept in English, but it concerns practical, context-dependant, value-driven, wisdom. He saw this as the most important of the three because it is about how techne and episteme are deployed towards ethical ends in specific situations.

Phronesis as planning’s defining characteristic

Planning scholars such as Bent Flyvbjerg have argued that phronesis is characteristic of, and should be central to our understanding of, professions like planning.

Planning is deeply political, and even relatively technical tasks like the submission of a planning permission require empathy and emotional sense. Public engagement very obviously requires this sense of the human experience and the values that communities hold. Indeed, the legitimacy of planning as a whole is grounded in the idea of decision making in pursuit of a shifting and subjective public interest, and the RTPI’s Royal Charter refers to the ‘art’, not just the science, of planning.

The risks of reforming decision-making systems for AI – and not for optimal outcomes

Phronesis is a useful concept because it reminds us that values, emotions, and the public interest are central to how planners make decisions – even when the tools being used are scientific or technical.

What this reveals about the profession’s relation to AI is that, as powerful a tool as it may be, it cannot (and should not) replace the expert judgement and discretion of professional planners, acting transparently.

There is a risk that in the push to harness efficiencies and insights, planning’s decision-making systems are redesigned to work well with AI, and not for optimal outcomes. In the world of planning, these often require the open consideration of the subjective, creative and emotional – not the rules-based and ‘black boxed’ systems often characteristic of AI tools. There’s no value in processing applications more quickly if the developments that follow are low-quality. Similarly, the public may feel little obligation to engage with processes and plans that no one has had a hand in creating.

Conclusion

Good or bad, AI will have a huge impact on society. The practice advice we published today makes clear that planners are facing a transformative shift, and that it is essential for RTPI members to develop a solid grasp of key concepts and technologies.

As Churchill probably didn’t say, ‘the further backward you look, the further forwards you can see’. Aristotle made clear 2375 years ago that ‘phronetic’ decision making is central to work like planning. AI powered tools may empower planners. But they are also tools to use with caution – supplementing and supporting planners’ role in decision making, not replacing them.