Gerard Crowley is a Policy, Practice and Research Officer at the RTPI

After more than 100 hours in committee and more than 1100 amendments, Ireland’s Planning and Development Bill has become the 900-page Planning and Development Act (PDA) 2024. By any measure it’s a big Act – and was described by the Minister of State for Local Government and Planning as “momentous not only in its size, but in its significance to nearly every aspect of people’s lives…”. Whilst experts agree with that overall sentiment – there is a very broad range of opinions about the impacts of the Act over time.

After more than 100 hours in committee and more than 1100 amendments, Ireland’s Planning and Development Bill has become the 900-page Planning and Development Act (PDA) 2024. By any measure it’s a big Act – and was described by the Minister of State for Local Government and Planning as “momentous not only in its size, but in its significance to nearly every aspect of people’s lives…”. Whilst experts agree with that overall sentiment – there is a very broad range of opinions about the impacts of the Act over time.

Looking into the immediate future, the Act will be commenced by Ministerial Orders in phases, supplemented and supported by updated planning regulations. So, for a transition period of around 18 months, elements of both the old and new planning law will apply.

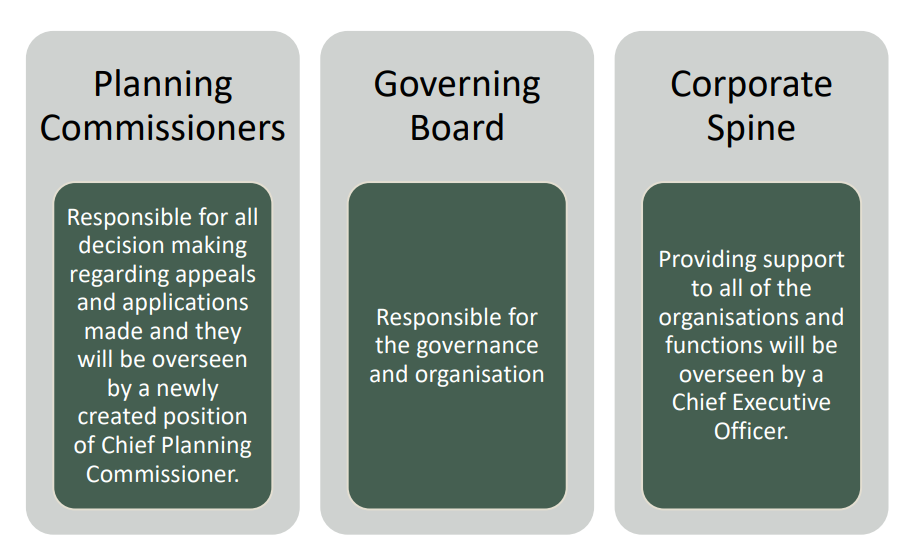

Departmental officials have been preparing for this transition period for some time, and we know that the first Ministerial order will include the establishment of An Coimisiun Pleanala (ACP), the renamed An Bord Pleanála (ABP). Whilst the change in name may seem fairly insignificant, the change heralds an increased focus on efficiency and transparency as well as new mandatory timelines for planning decisions. The new Act requires ACP to make decisions and adjudicate on appeals within 18 to 48 weeks – which will require a significant step change from the current situation. The most recent quarterly figures for ABP (Q1 2024) showed less than 20% of cases being processed within the proposed statutory time period – although since then the recruitment of additional staff has focussed on reducing the backlog and speeding up decision times. Let’s hope the transition into the new name and new responsibilities – shown in the diagram below - will go as smoothly and successfully as possible.

An Coimisiun Pleanala

Organisational structure:

Aside from changes to the appeals board, the new Planning Act makes a number of significant changes to the proceedings and appeals processes. Judicial review and third party rights of appeal are key features of the Irish planning system and there was quite a bit of discussion around these as the bill progressed. Key changes to the process include:

- The requirement to appeal a decision before seeking judicial review in the courts.

- Further restrictions are being placed on those taking judicial reviews.

- Instead of quashing a planning decision, the Court may direct that the relevant body amends a decision or document and place a stay on the judicial review proceedings until this has been carried out.

There’s a bit of wrinkle with the compatibility of the new provisions on judicial review with the Aarhus Convention however. In 2024, the UNECE’s Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee found that Ireland was in breach of the Convention by failing to provide for public participation and access to information on the environment in certain circumstances. The Compliance Committee then considered the relevant sections of the new Bill and found that there may be instances where public participation would not be facilitated. Members of the legal profession and a former attorney general have opined that the new legislation will not withstand challenge in the courts and recently, legal academics in an open letter to the national press wrote “the Bill is in breach of several legal obligations under EU and international law”. The Government had the opportunity to rectify this at amendment stage but chose not to do so.

This is a really important point about compatibility between international and national policy tiers. Waiting for the courts to adjudicate on the matter could hold things up significantly. If we look at the energy sector for example, state agencies have highlighted the need to ramp up the delivery of renewable energy capacity or we're not going to be able to make our 2030 emissions targets. Failing to meet those EU targets will result in fines of over €8bn. It will be important for all stakeholders in the planning process to be satisfied that the provisions of the Act are robust and Aarhus Convention compliant prior to commencement of the Bill and that the delays and costs associated with legal challenges are avoided.

Ireland is in the midst of a housing and infrastructure crisis – like the UK - and needs to find a way to increase development. Planning will need to play its part, but if the critics of the Planning & Development Act are right, the optimism regarding less delay and increased delivery may be unfounded. With an Irish election a couple of weeks away, perhaps a new Irish government will have the appetite to revisit and resolve this issue? Something to keep your eye on as Ireland gets ready to go to the ballot box.